Ritchie School Computer Science Student Ori Miller Utilizing Robotics Research to Make a Difference

We share a commencement profile on recent Ritchie School Computer Science Graduate Ori Miller and his research in utilizing robotics in impactful ways.

The Ori Miller of five years ago might have been hard-pressed to believe that his time at the Ritchie School of Engineering and Mathematics would bring him to where he is today.

“When I was an undergrad, I was not going to get my master’s. There was no way. I was very learning-challenged through high school,” Miller said. “But I always enjoyed absorbing knowledge.”

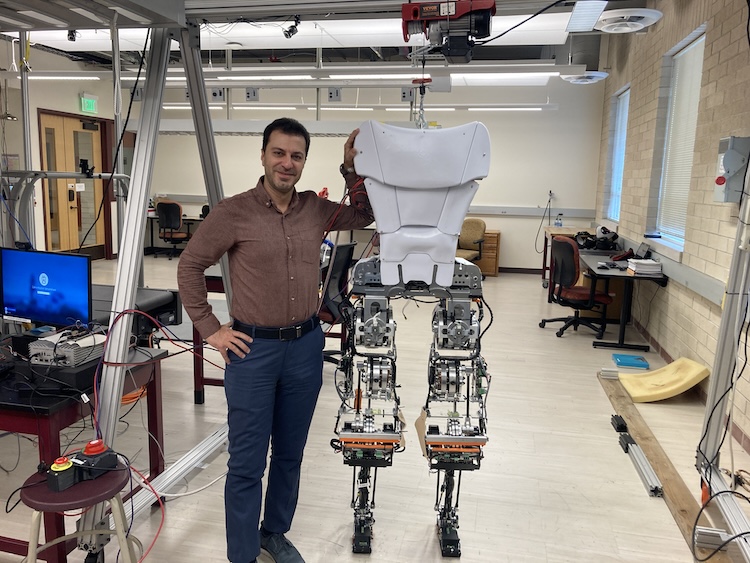

Now having graduated with a B.S. in Computer Science in 2022, Miller immediately began pursuing a Master’s in Computer Science with a research focus in robotics, which he completed at the end of Spring Quarter in 2024. Miller’s research interest began in January of 2021 with Dr. Christopher Reardon, a new addition to the Ritchie School at the time, having joined in October 2020.

Miller, a third-year student at the time, knew that research interested him, but he was not sure of the field he desired. To find out, he began cold-emailing professors, inquiring about open opportunities, until he was directed towards Dr. Reardon, who was just settling in after earning his PhD in 2016, followed by five years at the Army Research Lab in Maryland.

“It was incredible. Honestly, I think of it as an honor to be Reardon’s first student,” Miller said. “To get all of his attention and knowledge in a short amount of time really shot up my research experience.”

Miller enrolled in Dr. Reardon’s course “Software for AI Robotics” which teaches students how to work with robotics in a simulated, 3-D environment. For Miller, the experience was different than average. Following class, he had the opportunity to work directly with a state-of-the-art, mobile ground robot in the lab. His lack of experience in the field quickly gave way to a wealth of knowledge, but not without a fair dose of imposter syndrome.

As Dr. Reardon’s only researcher at the time, “It was overwhelming most of the time because I was the only person that [Dr. Reardon] could give this information to,” Miller said. “It was quick, which forced me to learn quick, but the excitement made up for the fear.”

Learning rapidly and honing his interests, Miller began conducting research on the confluence of artificial intelligence and robotics with the Autonomous Robots and Interactive Systems Experimental Laboratory (ARISE). For a project, he thought to start small: Robots that can play tag. A children’s game — “Sounds easy, right?” Miller joked.

Not exactly.

Miller gives humans a lot of credit. For a robot to compete with mankind in a game of tag, there is a lot it must process. The unpredictable movement of the human, the topography of its environment, and how the terrain can be traversed as fast as possible are just a few of the myriad considerations with infinite possibilities that a robot must take into account.

Miller is now pursuing a master’s degree in Robotics at the University of Denver under the wing of Dr. Reardon and his pursuit of the goal has yet to waver, despite the difficulties. “When I initially picked a robot that can play tag, I didn’t think that I would be doing it four years later,” he said.

The complication of autonomous navigation in complex environments is a central question for much of the research that Dr. Reardon’s ARISE lab. Robots that implement Miller’s research could one day track the movements of doctors throughout a hospital, delivering vital medical equipment with ease. They could also have a military application, coded to pass over terrain in the fastest, stealthiest manner during an operation. Or they could navigate environments unfit for humans, like a storage facility for transuranic waste.

The third of these is the goal of Miller’s role alongside the U.S. Department of Energy’s Waste Isolation Pilot Program (WIPP) 26-miles southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico. As “the nation’s only deep geologic long-lived radioactive waste repository,” the project’s goal is to “permanently isolate defense-generated transuranic (TRU) [low level] waste 2,150 feet underground in an ancient salt formation.”

Eventually, the salt formation will collapse and bury the radioactive material, but before that happens scientists and researchers are developing methods to safely deposit TRU with maximum efficiency and study phenomena associated with the conditions provided by the mines.

Miller’s area of study would prove useful in such an environment. GPS signals cannot reach half a mile below the surface, and although the salt’s absorptive effects make the caves safe for humans, it is still incredibly dangerous. Using robots primed with artificial intelligence to safely traverse and mark changes within the caves could prove useful. The code Miller is producing must allow the robot to navigate the caves safely, adopting rules that are unique to the mine.

“If there is a cave-in, we want to know where it is. We want to relay that to those on the surface,” he said. “If the ceiling sags 5 inches a year, we want to keep a map of it.”

It is his own research, however, where his passions lie. In research, Miller noted, when organizational and financial restrictions are irrelevant to the problem at hand, you only have yourself to rely on. And that self-determination pushes Miller to persist, even when a problem seems impossible to solve.

“It’s not that you work harder for yourself than you do for others, but if I have this high-level goal, I need to find a way to get to the end. You get to decide when to give up or change directions,” he explained.

Miller plans to gain some experience in the field before pursuing his PhD. After that, he has hopes to teach robotics, fulfilling his love for continuous learning.

But, in the short term, Miller will keep trying to teach robots to play tag.