Engineering Student Prints Device for Cutting-Edge Brain Research

To continue her cutting-edge research on Alzheimer’s disease, Lotta Granholm-Bentley had a not-so-simple request.

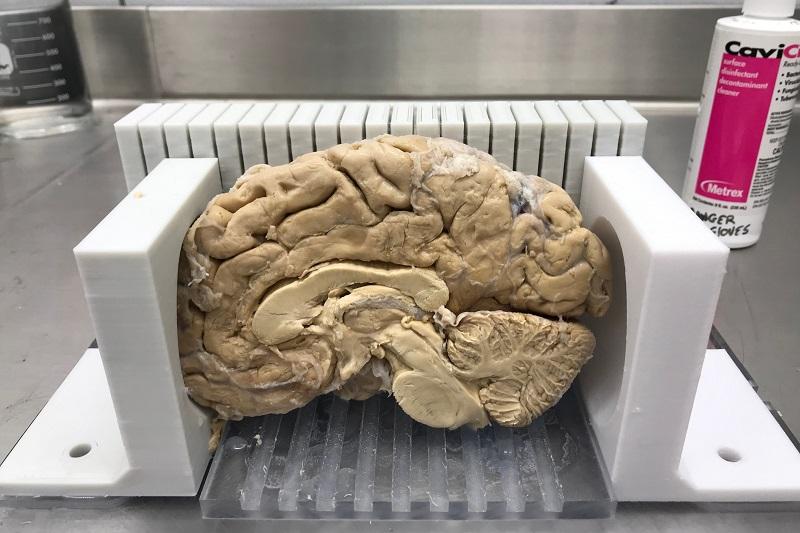

She needed a device that could hold a human brain and cut it into even, consistent slices, even if the brains themselves varied in size. And she needed nine exact replicas of the device to ship to her collaborators at universities around the globe.

The surprisingly simple solution, it turns out, lay just five floors below her office at the Knoebel Institute for Healthy Aging (KIHA). University of Denver undergraduate students in the Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science could get her what she needed faster, cheaper and better than anywhere else.

“Everything I bring to engineers here at DU, they say, ‘Sure, I can do that,’” says Granholm-Bentley, KIHA’s executive director. “No one has made a standardized, adjustable brain jig like the one we made.”

With funding from the Bright Focus Foundation, KIHA is exploring the relationship between Alzheimer’s — one of America’s most deadly diseases — and Down syndrome. The research focuses on the tau protein, which ordinarily helps nerve cells in the brain communicate with one another.

Read more about Granholm-Bentley’s research

When people suffer from Alzheimer’s, tau proteins collapse, allowing “tangles” to form in the brain and disintegrating the pathways between nerve cells. The same thing happens in the brains of people with Down syndrome. In fact, 80% of people born with an extra 21st chromosome develop Alzheimer’s as they age.

Granholm-Bentley, DU chemistry professor Martin Margittai and a network of researchers around the world are studying the tangles, trying to learn how early they form and catch Alzheimer’s in its earliest stages.

To do so, however, requires a standard sample from each contributing brain bank.

“The consistency is important because [we are studying] very discrete, small areas of the brain,” Granholm-Bentley says. “If we don’t slice just so, the same way each time, we’re not going to find it.”

That’s where Tim Bouraoui comes in. The DU junior is part of the Ritchie School’s new microfactory consultancy program. Created by fellow undergrads Jacob Goldman and Isaiah Silva and housed on the school’s Innovation Floor, the consultancy allows students with a knack for 3-D printing to work for real-world clients and receive compensation for their efforts.

The school provides each consultant with a 3-D printer, which the student is responsible for maintaining and upgrading if desired. In turn, the students take on projects from a variety of clients. They split the profits with the school. Once consultants hit a specified revenue limit, they keep the printer.

In this case, Granholm-Bentley approached Bouraoui with an idea and a rough model of what she was looking for. Over the course of three meetings, the pair created a 3-D drawing, produced a prototype and eventually a 3-D printed model.

“This is definitely one of the bigger jobs and definitely one of the cooler jobs that I’ve done,” says Bouraoui, who estimates he’s worked with 30 to 50 clients ranging from engineering classes to DU Advancement. “It offers a little bit beyond the design and manufacturing of it because it is tied to such a serious research group.”

Creating the brain jig was a challenge. Bouraoui had to find a way to make a medical-grade device — something that wouldn’t harbor bacteria and could undergo repeated, rigorous cleanings. Granholm-Bentley had sought similar products from other labs and medical schools, but ultimately, Bouraoui created a design that, after 36 hours of printing, could do the job at about half the cost.

“It’s the 3-D printer saving the day,” Granholm-Bentley says. With the jig, she adds, “we’re actually able to pinpoint where Alzheimer’s happens in the brain, how it spreads and how it’s different for different individuals. Then we can personalize medications and diagnostics based on that.”

For Bouraoui, the project has proved fulfilling on multiple levels. In collaboration with Granholm-Bentley, he is preparing a research paper, documenting his creation of the brain jig. It will be the first time the computer engineering major has been published.

But his experience with the microfactory consultancy has also yielded immediate results. This quarter, Bouraoui is in London, interning with E3D, a company that makes many of the parts students use on the Innovation Floor’s 3-D printers.

“A lot of my experience is due to being involved in the consultancy and seeing the limits I can push,” he says. “The exposure has opened my eyes to all the different ways I can use this method of manufacturing and how I can take advantage of what 3-D printing has to offer.

“It just helped out so much in providing real experience in how to talk to clients,” he says. “It’s been a great opportunity to gain some professionalism.”